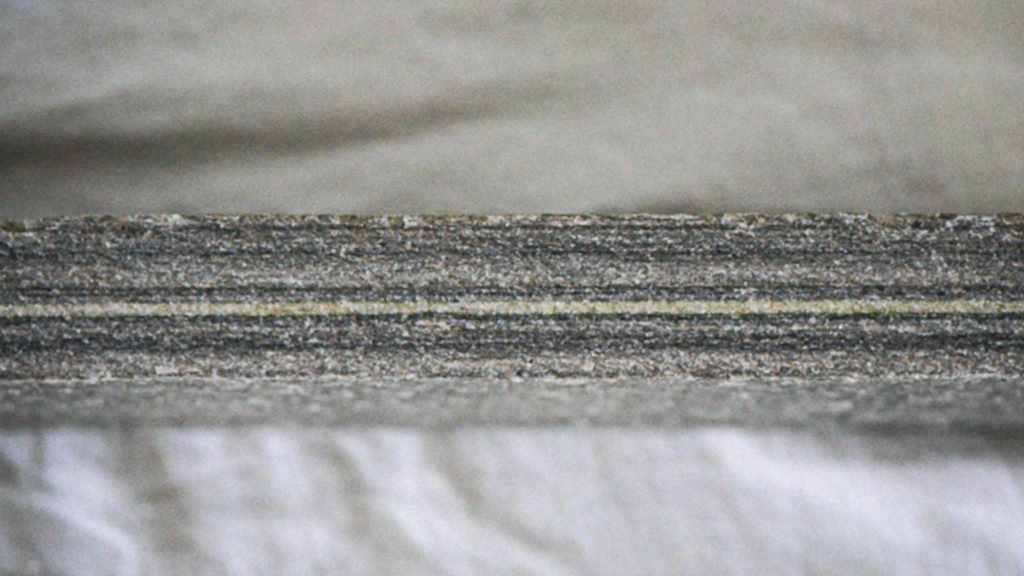

How can we make the most environmentally friendly choice of materials?

It’s not easy to find your way round the jungle of materials to which we have access today, and there are many things to consider. A product may be touted as environmentally friendly in production, but what happens to the environmental account if it has to be transported half-way across the globe? Or if it has a short life cycle and needs to be replaced in just a few years? How can we compare different environmental factors with each other? And what is the most important?